How to Free Yourself from the 7 Obsessions

To free ourselves from habitual patterns, says Valerie Mason-John, we need to see how they have become part of our identity.

Watch your thoughts; they become habits.

Watch your habits; they become stories.

Watch your stories; they become excuses.

Watch your excuses; they become relapses.

Watch your relapses; they become dis-eases.

Watch your dis-eases; they become vicious cycles.

Watch your vicious cycles; they become your wheel of life.

We meditate to uproot what the Buddhist teachings call samskaras. These are the mental impressions and recollections that have been psychologically imprinted in our minds by early childhood trauma.

We also meditate to loosen what the Buddha called the seven anusayas, which are obsessions or underlying habitual tendencies. If we really want to break deep-rooted habits, every one of us needs to become aware of the obsessions of sensual passion, resistance, views, uncertainty, conceit, ignorance, and the passion of becoming.

Every time we habitually react, the past is present.

Maybe you’ve made a New Year’s resolution again this year, performed rituals, done therapy, or tried plant medicine. But these seven habitual ways of acting out are still dominating your life and causing you misery. Why? Because the anusayas are rooted in ancestral trauma, intergenerational trauma, and epigenetic trauma. They have become part of your identity.

The thoughts that habitually run around in your head are part of your superego: they are giving internal voice to the adults in your past who harmed, hurt, and wounded you. Every time we habitually react, that past is present. It resurfaces.

I used to have a huge reaction if I was waiting for a friend and they were half an hour late. For some of you, someone being half an hour late wouldn’t be a big deal. But once upon a time, waiting for someone put my whole body into a crisis—palpitations, sweats, grinding my teeth. That’s because the memory was still in my body of the six-week-old me who was left somewhere by a mother who never returned. So when someone was late, my body memory was activated and I became deeply distressed.

This habit of reacting was only uprooted when I surrendered the identity of an abandoned six-week-old, and allowed that identity to die, in the painful gap of sadness, rather than habitually turning away from it in my distress. We transcend our habits by allowing a part of our superego to die.

Meditation: Thoughts with No Thinker

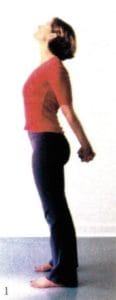

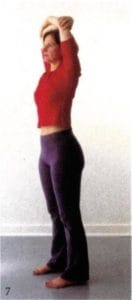

Become aware of the body by simply noticing what the body is touching. Notice your clothing and anything else touching the body.

The body produces sensations—it’s what the body does. So become aware of such sensations: heat, tickling, aching, throbbing. itching, pain, and so on. Notice that these sensations are either pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral.

Sensations trigger thoughts, so become aware of thoughts touching the heart–mind. Notice them without identifying with them, without thinking them, and without creating habitual grooves in the brain.

The heart–mind will produce thoughts, because that’s what it does, too. You don’t have to think them. You can be free of stinking thinking and have “thoughts without

a stinker.”

We work with thoughts by inhaling deeply, expanding the breath throughout the body, and then exhaling. Do this several times, and hopefully this will begin to weaken habits.